“Sai, ho!” A story of Pirates in Gibraltar – PT1

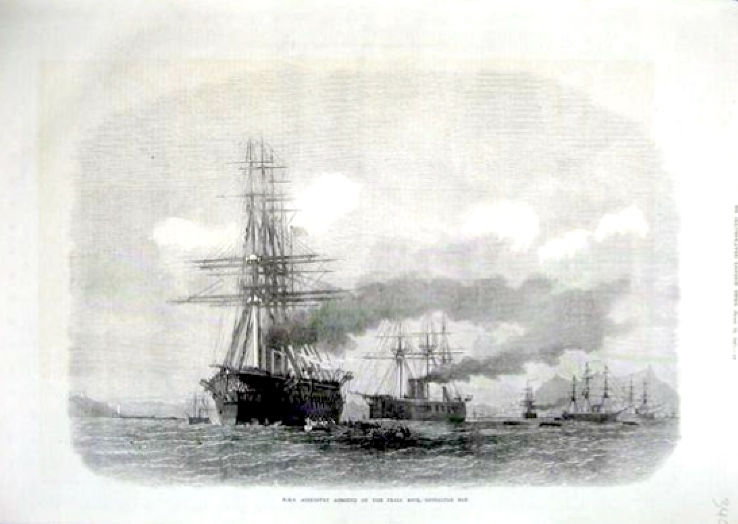

When anyone mentions “Pirates” one immediately thinks of the Caribbean, however, long before this, there were attacks on shipping in the Mediterranean. The Beys on the coast of North Africa, especially in Tunis, Tripoli and Algiers were preying on merchant ships trading between Spain, Italy, Greece and Northern Europe. Most of the large trading vessels were square rigged and were unable to manoeuvre very well as they were limited by the strength and direction of the wind. The Moors, on the other hand, operating from ports along the coast, were able to use small, fast agile craft, employing lateen sails and oars, manned by slaves captured from foreign ships were able to sail much closer to the wind. These vessels could head in any direction, able to overtake the lumbering cargo ships with ease. Not all the pirates were North African, many were renegade captains, Europeans who for one reason or another had thrown in their lot with the Berbers.

One of the most famous of these was Bararossa or Red beard. In fact this was not just one man but two brothers, Oruc (Aruje) and Hazir. (Kheir) They were born in Greece on the Island of Lesbos around 1470 from a Greek mother and a retired Turkish soldier, now a potter. They began their career by attacking ships in the Aegean Sea operation from their home base on Lesbos. Oruc was captured by the Knights of Rhodes (Crusaders) and served as a slave until ransomed by an Egyptian Prince in 1505 and reunited with his brother Hazir. They set up a base in Alexandria under the protection of the local Pasha. They then moved to Djerba, a port in Tunisia, south west of Sicily which enabled them to pillage ships coming through the gap between the North Africa coast and Sicily. This port became very rich as the result of this trade. The two brothers developed a hatred of the Spaniards and targeted their ships and raided their coastal ports. Oruc was hit by a cannon ball and lost an arm in one of his attacks on a Spanish stronghold in 1512.

The Sultan of Algiers was very unpopular among his people. In 1516 Aruj attacked the city and after killing the Sultan, took over the throne. Spain controlled part of the territory and for the next two years took on his hated enemy. During the siege of Tiemcan in 1518, he tried to escape but was captured, killed and put on display. His brother Hazir took over the throne and continued the struggle, this time with the support of and accord of Suliman I, the Turkish Emperor. Hacen Aga was made his Viceroy by the Turkish Sultan. Hazir was the seaman of the two brothers and spoke a number of languages as well as being a most accomplished engineer. He always admired his brother and in order to perpetuate his memory, he died his beard red like his brother.

He continued to harass the Spanish coast. In 1538, there were some forty Barbary captives living as slaves, some working on the fortifications, others at the oars of Spanish craft. These latter would often careen their master’s vessels at Los Dos Rios near Palmones where they would watch the coming and going of vessels into the port of Gibraltar and also get all the information they could about the fortifications and realised that the Spanish had let the walls and defences fall into disrepair also that the garrison was undermanned. Their hatred of the Spanish gave them the will to find a way to escape. One group of these oarsmen overcame their guards and made off in the ship that they had spent so much time rowing under the merciless whip of the slave master. Others pretended to convert to Catholicism in order to be liberated and eventually escape. A few climbed over the castle walls and descended by rope, eventually escaping to North Africa by boat.

Bararosa made a visit to Constantinople. While he was discussing business with the Emperor, his viceroy was approached by Caramani, who was a renegade Italian that had been a galley slave of Don Alvaro Bazan*, with the information on the state of the defences of Gibraltar, suggesting that it would be a easy place to attack, even if it was only for the booty and captives. The matter was passed to Barbarosa, now called Khier-ed-Din or Hayreddin, who was given the rank of Admiral of the Turkish Navy. In order to maintain the reputation of his dead brother he died his beard red. A number of his advisors were gathered in Algiers, among them was a Sicilian named Azenaga. It was concluded that Gibraltar was an easy target for their vengeance and probably booty was to be had. Calamani had a number of sailors who, had been slaves in Gibraltar with him, and knew the place intimately..

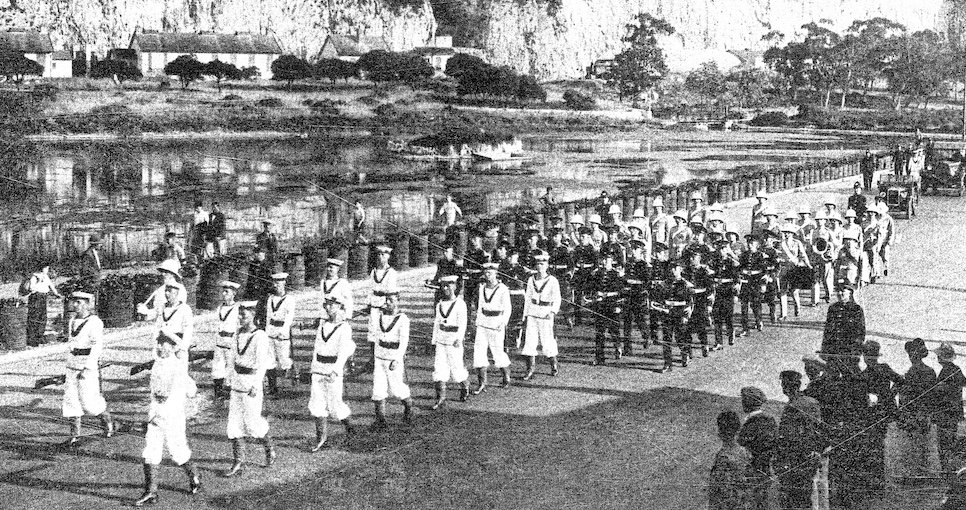

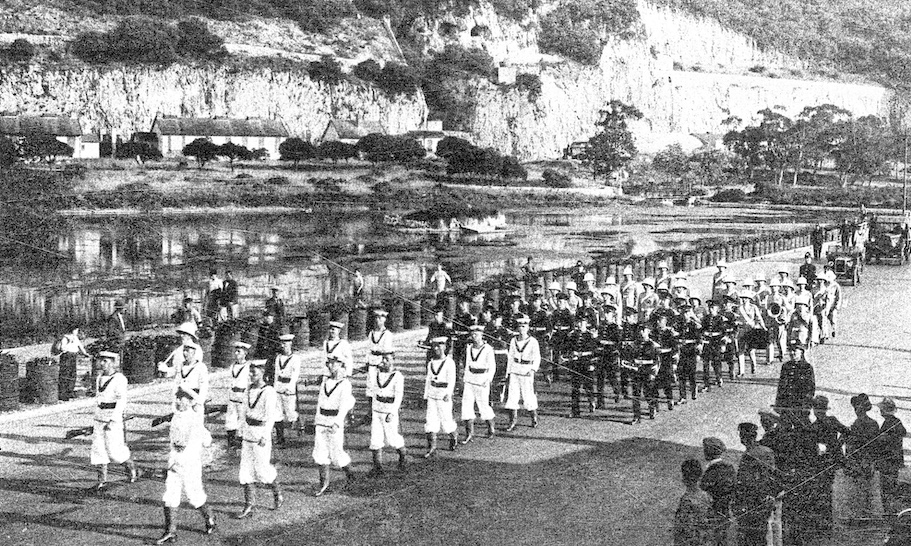

A plan was swiftly drawn up. A fleet of three galleys. Five galliots, six fustas and two brigantines, 900 oarsmen, most of them Christian captives, under Ali Hamat, a renegade Sardinian, and two thousand troops under General Caramani, Among the Captains, selected for their bravery and knowledge of the coast were, Mohamad and Mami both renegade Greeks, converted to Islam, Alicaur and Martin Juan and Daide all escapees from Don Alvaro’s ships at Palmones. Alisoja was a captain of one of the brigantines, also an ex-slave, the remaining captains were Turks. At this time most of North Africa was under Turk domination but Morocco was the exception.

The fleet left Algiers on August 20th 1540. They stopped on route at Cape Entrefolcos where they sent a brigantine out to find the location of the Spanish fleet under Don Bernardo de Mendoza. The vessel soon returned to report that the Spanish fleet was still in Sicily. The invasion fleet was sighted by the Spaniards from Melilla who sent word across to Malaga and from there by messenger to Gibraltar warning them of the approach of the enemy. The messenger was received by Gomez Balboa in the castle and immediately called Alonso Moreno,

the mayor and the other councillors to a meeting in the Castle Tower. The Magistrate, Juan de Lujan was at this time in Grenada. The Council ordered guards to be put on alert and that a message be sent to Tarifa and Cadiz to warn them of the fleet approaching from the East. The defenders were now very worried about the state of the city’s defences. The confidence that the council had in the city defences was misplaced but Pedro de Piña laughed at the warnings. Now they would suffer the consequences, the city was undefendable. Canons and powder that had been left by Bazan in 1538 were useless as they were dismounted. Utter confusion reigned. Nobody warned the surrounding countryside of the impending danger and the people in the town went about their business as if there was nothing to worry about.