WS21S Operation pedestal

PART 2

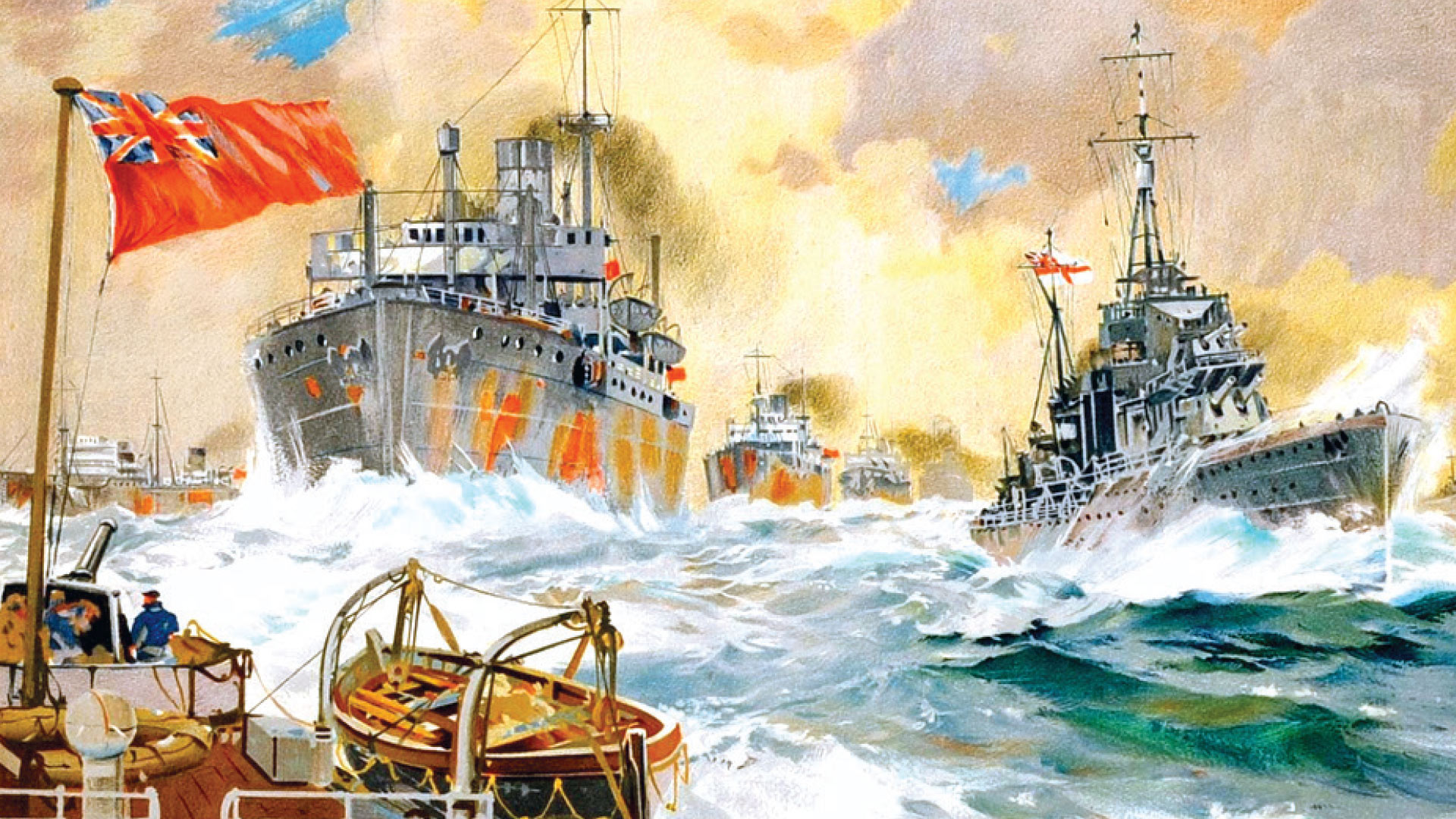

This article is a tribute to all seamen that sailed the seas during the war to keep us supplied. Whenever Poppy Day is mentioned, people immediately think of the soldiers that died. Only afterwards do the Merchant Seamen and Navy get a mention. Without the heroic action of these men, neither the Army nor the Airforce would have been able to continue the battle and we civilians would have starved. I

t must be remembered that there were seamen of many nations both from the Commonwealth, the United States and occupied Europe fighting under the Red and White Ensigns and flags of many other nations. This is also a tribute to the people of Gibraltar who played no small part in keeping the ships repaired and supplied.

Britain Never Stood Alone.

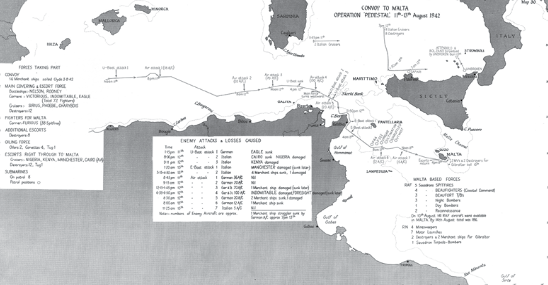

To most of us, the title means nothing. It was, however, one of the most important events in the battle for the Mediterranean in World War II.

Italy entered the conflict on June 10th 1940 declaring war on Great Britain.

Mussolini had a very strong naval capability in the Mediterranean which posed a problem for the Allies fighting in North Africa. Rommel depended on supplies from Italy to enable the Axis forces to continue the fight in North Africa. Unfortunately for him, Malta was in the middle of their supply route and was a thorn in his side.

The Allies likewise had the problem that Malta had to be kept supplied in order to maintain the attacks on Rommel’s supply route. With Sicily only about 200 miles from Malta, both German and Italian aircraft were able to attack Malta with impunity, less than two hours away.

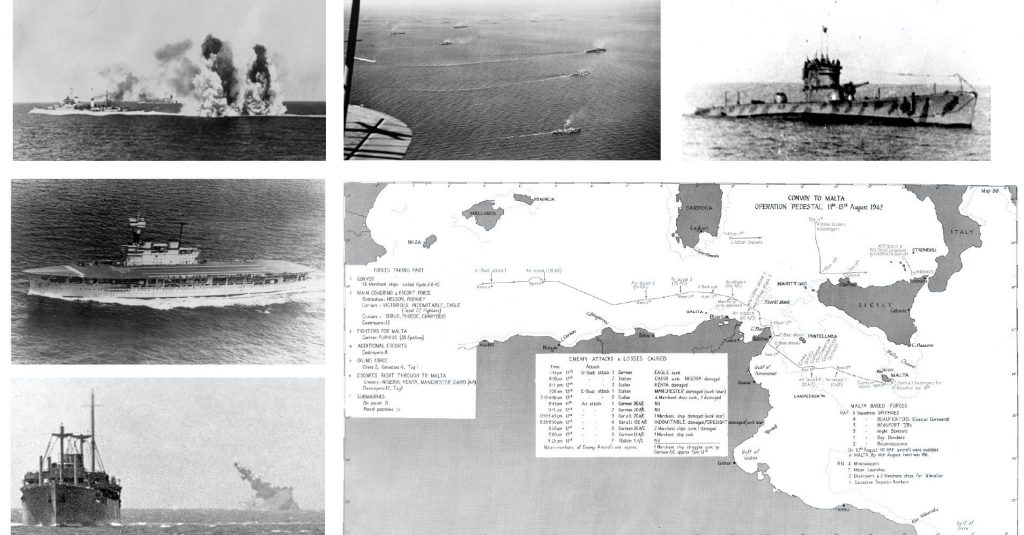

On 12th the convoy entered the dreaded “Canale di Sicilia” where HMS Kenya was hit by a torpedo from the Italian submarine Alagi. A torpedo hit the bow and blew off a large section around the waterline. She returned to Gibraltar.

As the ships passed Pantellaria, the island in the middle of the Straits of Sicilia, HMS Manchester was attacked by motor torpedo boats MS16 and MS22 of the Italian navy. Two torpedoes struck the ship amidships on the starboard side flooding the boiler room and magazine also damaging three of the propeller shafts and causing a 12° list. The ship was soon out of control and attempts made to scuttle her were in vain, so she was finally torpedoed by HMS Pathfinder. The destroyers HMS Eskimo and Somali were sent back to help Manchester but arrived after she had sunk so they picked up survivors from Manchester and then made for Gibraltar, arriving on afternoon of 15th.

The destroyer HMS Ithurie attacked the Italian submarine Cobalto with depth charges and after a gun battle rammed and sunk her, but the Ithurie received damage to the bow and had to return to Gibraltar for repairs.

The cruiser HMS Charybdis was screening the carrier force when two bombs landed on the unarmoured part of the flight deck of HMS Indomitable forcing her to leave the convoy and head for Gibraltar. All the aircraft that were airborne at the time landed on HMS Victorious, however her deck was also damaged by a dud aerial torpedo.

The destroyer HMS Foresight was torpedoed by motor torpedo boats, she flooded aft and was unable to steer and taken in tow heading for Gibraltar but became unmanageable so was later sunk by HMS Tarter.

The Axis losses were relatively light, consisting of two submarines, two motor torpedo boats two cruisers damaged. The latter was part of the action off the north of Sicily, referred to above.

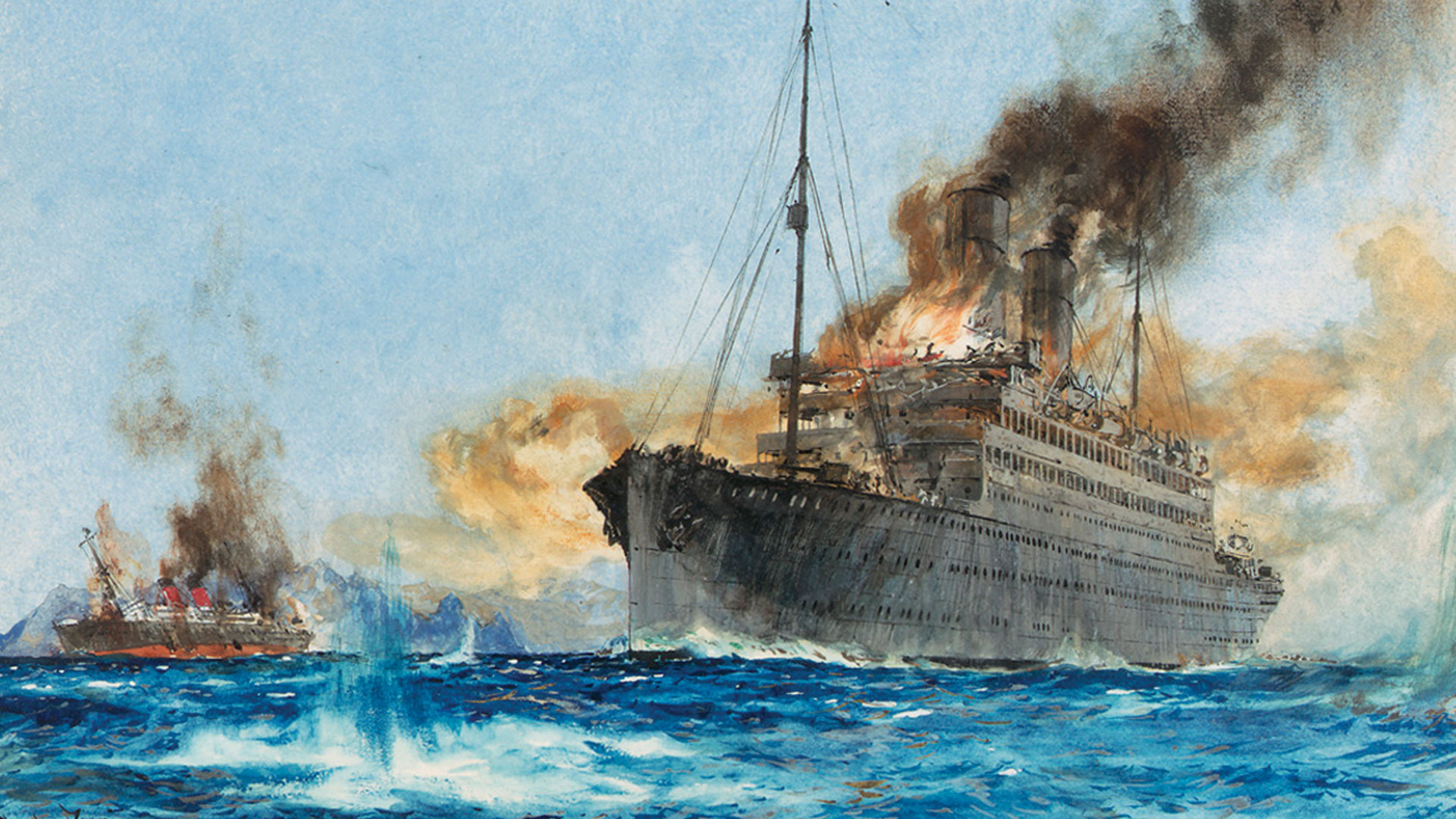

Up to now only the naval actions have been covered, the merchant ships were the object of the exercise. This consisted of fourteen ships.

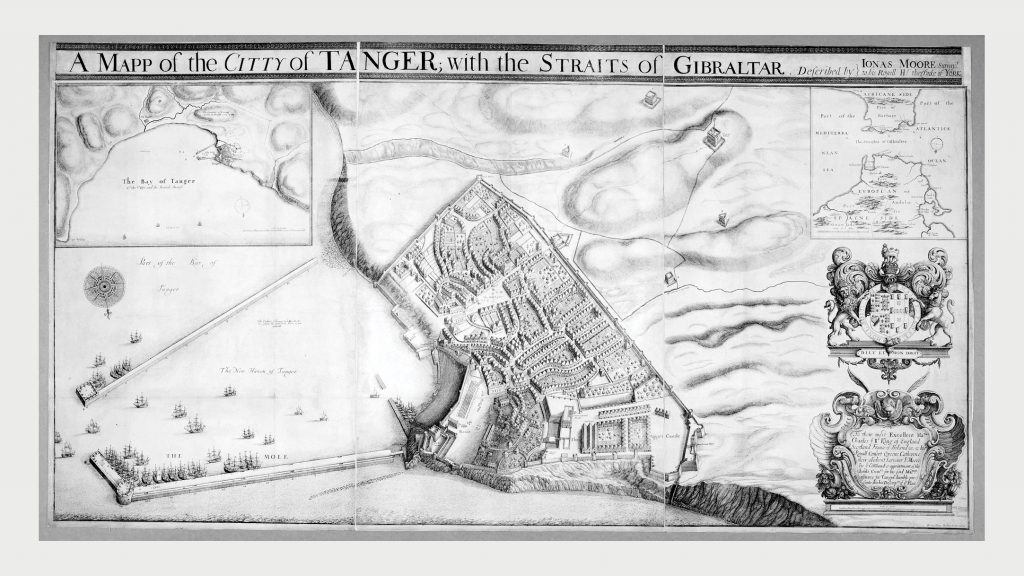

The convoy entered Gibraltar on august 10th in heavy fog. Spies in Algeciras, Spain and Ceuta across the Strait in North Africa failed to spot the passage of the convoy through the Strait of Gibraltar in the fog, but were spotted by German reconnaissance aircraft in the morning and not long after the attacks commenced.

Ohio, a US tanker carrying diesel and kerosene, was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Alagi on evening of 12th and hit several times before being towed into Malta on 13th.

Melbourne Star, cargo ship carried aviation fuel, kerosene, shells and fuel oil. Set on fire by flying wreckage from the exploding Waimarama. Arrived in Malta on 13th with cargo intact.

Dorset disabled by bombs from Stuka attack, engine room flooded cargo on fire, abandoned and again bombed. Sank on 13th.

Waimarama, cargo ship with aviation fuel, and ammunition was hit by attacks by MTBs, blew up and sank in seconds on 13th.

Rochester Castle hit in No3 hold by two torpedoes from German E boats but was able to continue. Arrived on 13th

Brisbane Star, cargo ship, with a cargo similar to Melbourne, was hit by a torpedo from the Italian submarine Alagi, which badly damaged the bow. Later attacked by torpedo bombers but the torpedoes were dud. The ship was able to reach Malta on 14th with her cargo intact.

Port Charmers was saved by a torpedo being caught in a paravane cable and safely released, arrived on 13th

Almeria Lykes torpedoed by German E boat S36 and then again by Italian MAS554. She was abandoned and scuttled on 13th

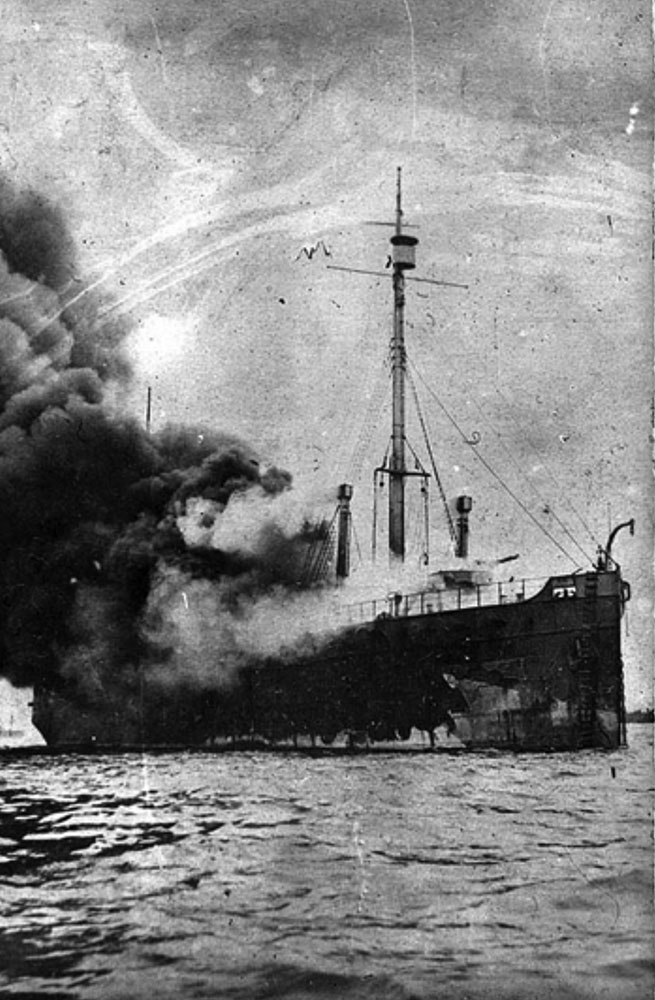

Clan Ferguson hit by bombs and then by torpedo from Italian submarine Alagi which explodes the cargo of ammunition and she sinks on 12th

Deucalion hit by aerial torpedo, set on fire and blew up following a torpedo attack by the Italian submarine Bronzo. Sinks on 12th

HMS KENYA, BRITISH FIJI CLASS CRUISER. JANUARY 1941, AT SEA. (A 2785) Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205137134

Empire Hope set on fire by bombs and abandoned sunk by HMS Penn. The Italian submarine Alagi also claimed this sinking on 12th

Glenorchy torpedoed by Italian MTB MS31 sank on 13th

Santa Eliza with a cargo of aviation fuel in drums, hit by torpedo from MTBs, set on fire, abandoned. Attacked again and another fire started. Sank on 13th

Wairangi torpedoed by E boat. Engine room and No3 hold flooded. Sank on 13th

The destroyers HMS Penn, Bingham and Ledbury were used to rescue survivors from the various ships. HMS Ledbury steamed into a burning sea of fuel on one occasion to rescue survivors from Waimarama.

Of the fourteen ships, only five reached Malta with 29,000tons of cargo, fuel, and ammunition. Enough for ten weeks was delivered to the embattled island but at what cost? The royal Navy suffered 426 dead, the Merchant Navy, 120 men. This figure was obtained by adding the list of casualties for each ship, found on the internet and may not be accurate.

This article has concentrated on actions by Italian and German naval forces, but much of the damage to the convoy was done by Italian torpedo carrying aircraft and German Stuka dive bombers. Use was made of radio controlled aircraft, parachute released bombs and torpedoes that circled in an increasing spiral. The effectiveness of these weapons is in doubt.

There was also an action at the same time, as mentioned above, between British submarines and Italian cruisers along the north coast of Sicily.

There is some confusion about attacks by the motor torpedo boats, some references claim all to be Italian, others say, some German E boats, no doubt it was a combination of the two.

Apart from the main naval force, there were a number of other ships referred to in various reports as taking part in Operation Berzerk but do not get a mention in the actual action other than the tug Jaunty. The four sloops Jonquil, Spiraea, Coltsfoot and Geranium were escort to the two RFA tankers, Brown Ranger and Dingledale and presumable continued with them after the final fuelling on 10th August to Gibraltar, otherwise the RFA tankers would have been prime targets as was the Ohio. The only other vessel in the list was the salvage ship Salvonia. What part she played is unknown.

There is reference above to a paravane. This was a torpedo shaped float with a stabilising fin which was streamed out from a warship during mine sweeping operations to snag the tethering wires of mines.

The following is a list of the destroyers attached to the convoy.

Including those escorting HMS Furious:-

HMS Ashanti,

HMS Tartar

HMS Antelope,

HMS Vansittart,

HMS Westcotte

HMS Wrestler,

HMS Eskimo

HMS Ithuriel,

HMS Laforey

HMS Wilton,

HMS Wishart,

HMS Bicester,

HMS Bramham,

HMS Derwent,

HMS Foresight,

HMS Fury,

HMS Icarus,

HMS Intrepid,

HMS Keppel

HMS Lookout,

HMS Amazon,

HMS Zetland

HMS Quentin,

HMS Ledbury,

HMS Pathfinder,

HMS Penn,

HMS Malcolm

HMS Venomous

HMS Wolverine

HMS Lightning

Other ships (the four Flower Class Corvettes were escorts

to the RFA Tankers during

Operation Berzerk)

HMS Coltsfoot

HMS Geranium

HMS Jonquil

HMS Spirea

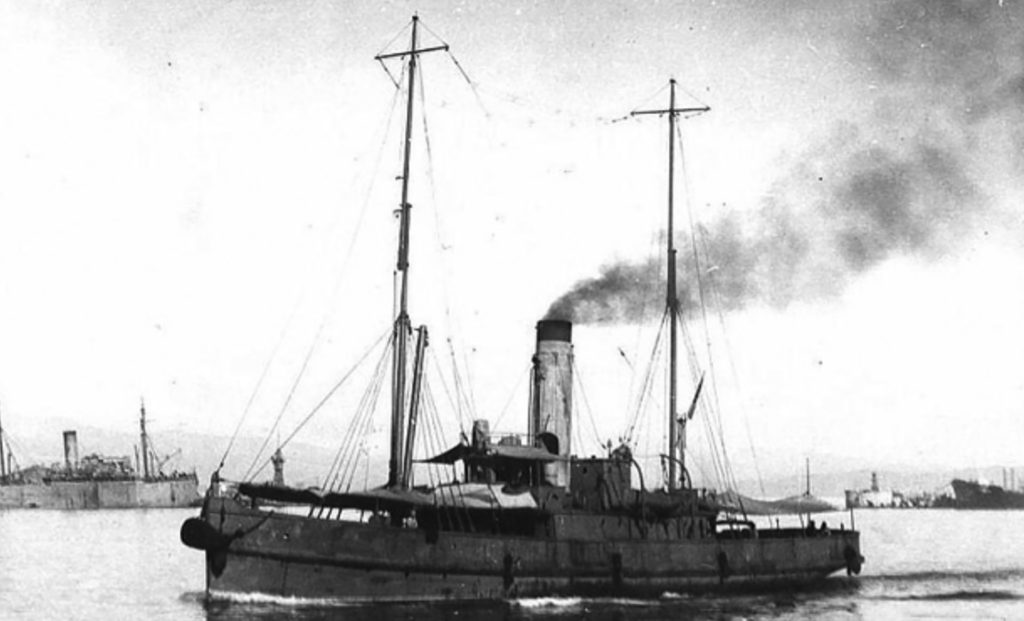

HMT Jaunty

HMS Salvonia (Salvage)

RFA Dingledale

RFA Brown Ranger

The story of the US tanker Ohio is an epic in its own right and may be covered at some future date.

Acknowledgements

I have used the internet and Wikipedia extensively as well as books from my own library to cross check the information as much as possible. I have found many glaring errors in many reports and inconsistencies in others, even by eye witnesses, which I hope I have managed to correct, I would welcome any comments on the subject.