Battery Fifteen

A fictional account. Taken from the Graphic Magazine of 1901

Birvaneff laughed without any trace of a sneer. He was cock-sure, that was all, but none the less irritating. I pulled him up sharply.

“You are only bluffing,” I said. “ You may know about our guns at home; all the world does, I suppose, since nowadays half of them come from Germany ; I daresay you have plans and specifications of our ships—we have of yours ; but there are still a few secrets that Britain keeps to herself just a few.”

He only laughed again and lit a cigarette. He was quite pleasant about it, but still most annoyingly confident.

“Not one!” he declared, “not a single one! We know you inside and out. Harbours, ships, railways, batteries, rifles, and men—we have information of everything, down to the boots and clothing in store. I believe I could tell you within a hundred pairs how many “ bullswools,” as you call them, have been returned as imperfect within the last month to your army clothing department. I’ll inquire when I get back and write to you if you like. You can compare and see how near I come.”

“Oh, hang your statistics! “ said I. “ You can get those from any clerk, who may or may not be a foreigner, and in the clothing depot often is. Numbers of saddles and horses and men and rifles are not hard to come at. London is a sieve of information. But here, in Gibraltar things are a trifle different. Could you give me the armament of Battery 15 in the second gallery, upper tier, for instance?

He didn’t answer me at once. He looked at me with a sort of meditative inquiry.

“I dare say I could—if you gave me time,” he said, slowly. “But, then, you couldn’t check the information yourself.”

“Oh, but I could!” said I.

“You could?”

“Yes, with infinite exactness.”

He stared at me thoughtfully. “I thought the information was kept secret even in your own army. We know, of course; we make it our business to know. But I understand that the upper tier armament is entirely in the hands of the superior officers of the artillery and engineers. I will flatter you by saying that they, as a rule, are not to be corrupted.”

I nodded and grinned. “We are not flattered,” I answered, “but we take your compliment in the spirit in which it is offered. As a member of the incorruptible body I thank you.”

“But how will you check my information, then?” he asked. “It’s my own battery,” said I, simply

and Tring laughed, for I certainly had scored. Birvaneff was not put out.

“That, of course, is conclusive,” he agreed. “But all the same, when I return home I’ll see if I can’t surprise you with my accuracy. I have not the information at my fingers’ ends, and can’t give it off-hand. We don’t in the least mind your knowing how much he know. It is because we can gauge your strength so exactly that we don’t pick a quarrel. But it must come in time, you see. We are growing steadily. We shall be ready one day. Then—“

“Then?” said Ferrers.

“Well, let us hope it will mean promotion for us all,” answered Birvaneff, sweetly.

He settled down to play sixpenny nap with three of the fellows after that, and as one of my sergeants was ill in hospital I strolled over to see after him. When I got back an hour later Birvaneff was gone and the chaps were discussing him.

“See you propose him as honorary member of the mess?” said the Colonel.

“Yes Sir.”

“Where did you pick him up, Strange?“ I explained that he was in the Prince’s suite, and that he brought a letter from my brother in England. “You will see for yourself, sir,” said I, as I drew it from my pocket-book and handed it to him.

The letter said that the bearer, Hetman Birvaneff, of the 31st Regiment of Oural Cossacks, had been attaché at the Russian Embassy, was everybody’s friend, and a thorough sportsman. He spoke English like a native, liked a good dinner, and knew a horse and a cigar. He had given my brother famous introductions last winter in St. Petersburg, and the former therefore hoped that I would return this hospitality vicariously for him while. The Cossack captain, who was attached to Prince Basil’s staff during his Mediterranean tour, sojourned at Gibraltar. Anything that I could do to give Boris Birvaneff a good time would be thoroughly appreciated by the writer, who trusted I kept fit, was seeing good sport with the Calpe, and remained my affectionate brother.

The Colonel handed it back with a nod of approval.

“Why, certainly,” he said.

So for the next fortnight we saw a good deal of the Hetman of the 31st Regiment of Oural Cossacks, and the more we saw of him the less reason we had to dislike him. For a Russian, as the Colonel put it, he seemed a thoroughly good sort. He talked, he thought, apparently, and, lastly and especially, rode like an Englishman. He got two days’ leave from his Prince, and we took him over to the Tent Club camp at Tangier. The next day he took “first spear” out of Ferrers’s mouth, so to speak, with a horny old grey-back of a boar in a decisive fashion that made us fairly blink. “Good Lord!” was the only remark Ferrers made; but he looked from Birvaneff to the boar and from the boar to Birvaneff as if lie thought there was some extraordinary mistake somewhere. Ferrers is rather our top line man at pig-sticking, and got unmercifully chaffed for many days after.

But what we liked particularly about Birvaneff was that with all this sort of thing he carried no side. He treated his own riding and our riding- we had all been members of the Tent Club for over a year, you must remember-as a simple matter of course.

“Ride? “ he said, with a sort of wonder, when somebody hinted that his horsemanship was something above the average. “Why, of course I ride! I am a soldier, a cavalry man.”

We pondered that if the God of battles ever sent the 31st Regiment of Oural Cossacks full tilt against one of His Majesty’s batteries of R.H. A. there would be some fine swordsmanship, that is to say, if the troopers rode like their Hetman.

We liked him even better after that, and, in some ways, I think he returned the liking. He wandered in and out of the anti room of the mess all day long. Most evenings found him there, unless the Prince had need of his society, or when he dined with the Governor, which he did once it twice. He was good enough to take a special interest in me, and always darting professional questions at me. Some of these were a bit awkward to answer.

I can’t see how you keep a very tight supervision on your guards and sentries through all these miles of galleries, he remarked one evening. You come in at the gated with a rattle of keys. The guard turns out. Of course the sentries pass the word along that the Officer of the Day is on his rounds. He must be signaled from post to post long before he gets to them.

Between whiles they must do much as they like.”

I ginned.

“Yet we do prevent it,” I said.

“How?”

“I thought you knew as much about these things as we do ?” said I.

He laughed good-naturedly.

“Yes, you score there, He answered” I spoke too confidently. Still, I don’t see how you can avoid the thing happening as I say.”

“ Well, we don’t go in with a rattle of keys and turn out the guard, that’s all,” said Ferrers, who should have known better. I saw the Colonel frown.

Birvaneff stared at him with that look of musing inquiry which he often wore. Then he nodded.

“Why, of course,” he said ”I should have thought of that. There are secret entrances known to certain of the officers alone?”

We all laughed at his artless way of putting it.

“I think a hand or two of nap will be better than all this professional shop,” said the Colonel, quietly. “Have you time for a game before you go, Strange? For I was officer of the night.

When I left for my rounds an hour later Birvaneff came with me. We walked for a few hundred yards together before we reached the point at which we had to separate—he for the town and I for, well a point on Flagstaff Hill which many field officers (but non below that rank) knew well. It is rather lonely there on the plateau where the road divides going down past Ragged Staff towards Alameda, the other turning along towards Europa Point and the Monkey’s Cave.

“You are confirming my hypothesis, my dear Strange,” said Birvaneff as we shook hands. Where is the guard that accompanies the officer of the day? You are going to surprise these dear gunners of yours, as I said.”

“I don’t think I am ever much of a surprise to them,” said I.

“I should like to come with you and prove it,” he mused.

I laughed. “Good-night,” said I. “See you tomorrow?”

He seemed lost in a fit of meditation.

“Good-night,” he answered, looking up with a start. “Yes, tomorrow, if you’re not tired of my ceaseless company. Hallo” He was staring out seaward, pointing to something over my shoulder. “What can that be?”

I wheeled round, gaping southward towards Africa. In the misty darkness I saw nothing but the twinkle of the stars and the riding lights of the shipping in the bay. They were dim and growing dimmer. A heavy fog was closing in from the Atlantic.

Two hands whipped sharply past my cheeks, and something soft, stuffy, and smelling sickly sweet was pressed over my mouth and nostrils. I struggled, I fought, choked; the breath seemed to drown my lungs in a flood of molten lead. I kicked convulsively with my heels behind me, but nothing loosened by a hairsbreadth the grip of the strong arms that were locking my head and shoulders. I might have been clamped by iron hands. Then a sort of weakness, deadening paralysis, seized my muscles. My arms fell against my sides. My head drooped to my chest. There was a rushing murmur like the drone of a torrent in my ears. I slept.

I woke reluctantly and drowsily. I tried to mutter words, but my tongue refused its office. There was a terrible pulse of pain at its tip. It was skewered by a silver toothpick, I afterwards found, to my lips outside my teeth. I was dumb, and the dull pressure that was at my wrists and elbows told me that I was bound. A lead weight was pressing my ankles to earth.

My eyes grew accustomed to the darkness and I realized my position. We were in the shadow of the cliff beside the private entrance to the galleries.

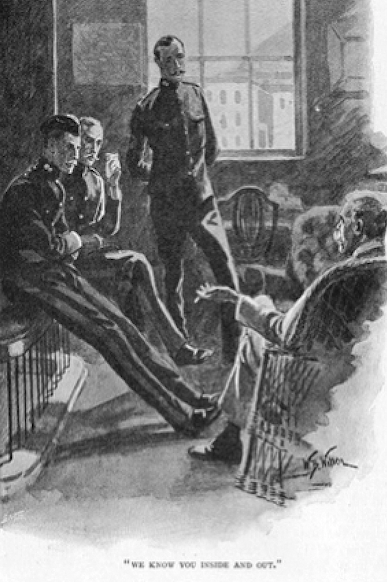

Sitting across my legs, Birvaneff was leaning forward to peer into my face. I saw that he was examining me to discover if I had regained consciousness. His lips dropped to my ear and he whispered :-

“Are you awake? Move your right foot if you are.”

For a moment I hesitated, but what was the good of deceiving him? I shuffled my right foot.

I could tell by the gleam of his teeth that he grinned.

“You see, I know the secret of the entrance,” he said. “My question in the mess was to find out if you did. But unfortunately I do not know the key-word to this lock. You must open it, my friend”.

The blood flushed to my face with rage. I shook my head violently. The wicket lock is opened by a different word every night, known only to the Governor, the town major, and the officer of the day. The scoundrel! I open it! I’d see him most particularly and completely hanged first.

His right hand moved towards my breast. Something gleamed silkily in the dull shadow and I felt a sharp prick of pain.

“This stiletto is exactly over the centre of your heart, my good Strange,” he whispered, quietly. “Think, if you please, a little more discreetly. Life is good, very, very good. You stand well in your profession. The Calpe are showing capital sport. It would be dark and squalid and unnecessary to end it all here. Think of the warmth and the light and the jollity of the Tent Club campings for instance. And they tell me, too, that you are going to get married.”

A vision of Nellie’s face seemed to rise from the darkness to tempt me. Oh, it was a dark and terrible trap in which I was taken. You who hear my tale in the light, and with not an hour’ of your

Life at stake, can hardly understand the agony of that moment. To be flung out of life suddenly, treacherously; to die, not like a man, but like a cornered rat; to have no time to think, to drop as in a moment into the abyss of eternity, eternity. God forgive me. I shuffled my foot again.

He nodded as he rose warily off my legs.

Article supplied by History Society Gibraltar.

Email: historysocietygibraltar@hotmail.com