This is how we can save them

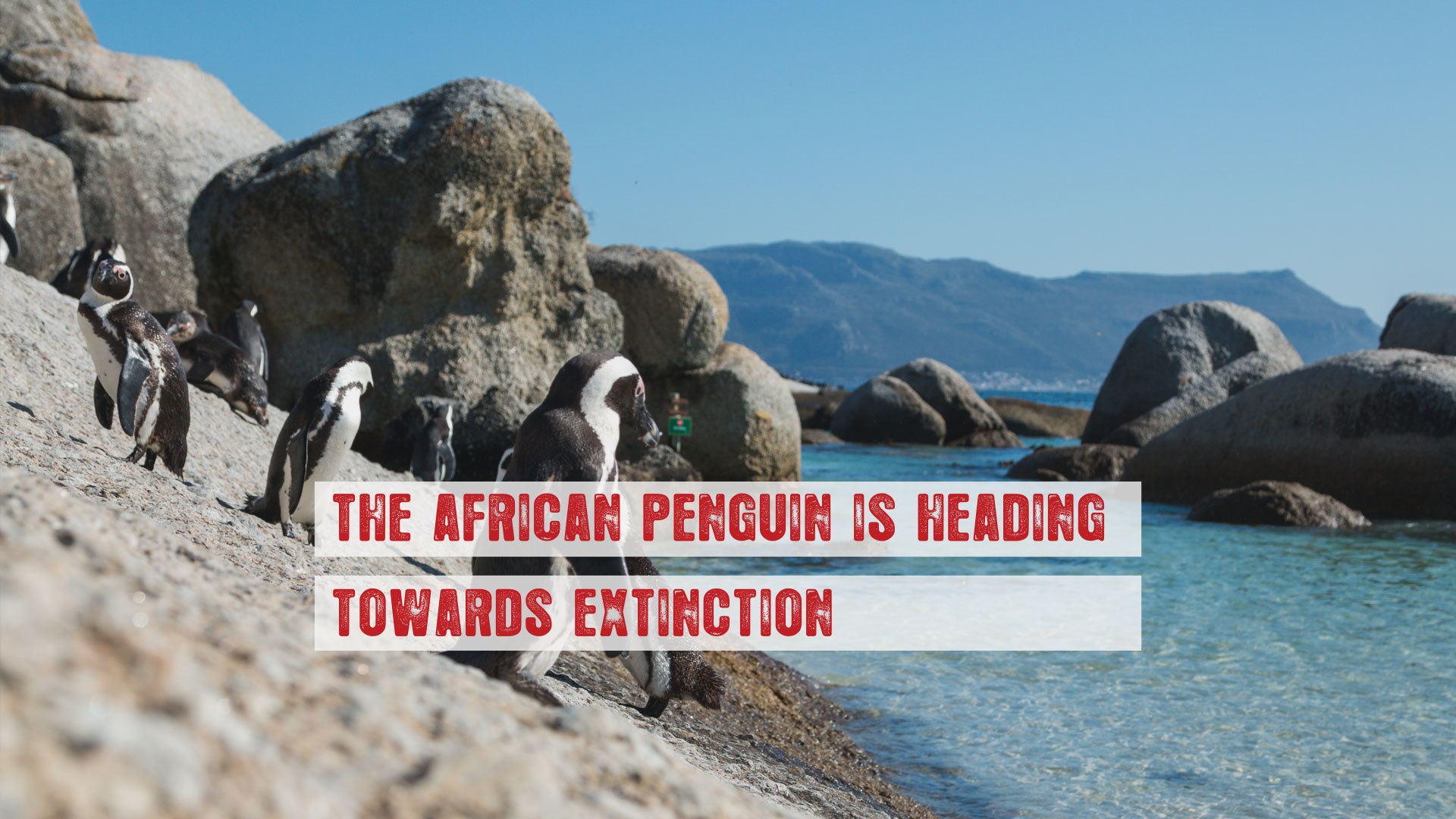

There’s a magical moment of transition when a penguin crosses from land to water. Earth-bound they are slow and cumbersome; as soon as they enter the ocean they become sleek and agile, diving with torpedo precision to forage for life-sustaining fish. That is, assuming there are fish to be had.

Last week I drove out to Stony Point near Hermanus in the Western Cape, to assist SANCCOB (the Southern African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds) with a release of rehabilitated African penguins. As I opened one box and watched its eager occupant waddle toward the water, fat and glossy with good health, I was struck by the difference between him and some of the resident birds.

I heard the despair in SANCCOB marine scientist Lauren Waller’s voice as she pointed out birds that likely wouldn’t make it through the next few days. I’ve visited penguin colonies all over the southern hemisphere, but until now, I’ve never seen a starving penguin. It was eerily reminiscent of the malnourished polar bears I’ve seen in the north.

Competing for food

Many of these wild penguins were moulting – something penguins do every year. The birds stay ashore for up to 21 days to shed and regrow their protective feathers. Because they can’t swim during their moult, they need to eat plenty before they come ashore to make it through their fast. These birds should have been at their fattest, but a good number of them were seriously emaciated, their breastbones pointing through their feathers when they fanned their wings.

The resources in our oceans are not endless, and they are no longer abundant, thanks to the combined threats of global warming, pollution and industrial overfishing. Standing on that rocky shoreline it became clear to me how acutely the African penguin is feeling these changes.

Some of these birds may have swum hundreds of kilometres to find food. Marine researchers from BirdLife South Africa recently discovered pre moulting penguins from Dassen Island turning up in De Hoop nature reserve some 350 kilometres away. Swimming such a long distance around Cape Point is not the best strategy when you’re trying to put on weight, but these birds have no choice.

Functionally extinct

The science is clear: the African penguin is likely to be functionally extinct on the west coast in less than 15 years, unless we take immediate action.

Functionally extinct means that a population has declined to the point where it is no longer viable, and can no longer produce a new generation.

When surveys began in the early 1900s there were 3 million African penguins. Since then we have lost 95% of the population, and their numbers continue to drop. In 2000, there were an estimated 53,000. Today, there are just 17,700 breeding pairs.

They are now more vulnerable than the white rhino, the polar bear or the giant panda.

Oil on water

If the situation wasn’t dire enough on the west coast, a new threat has emerged on the east coast, with offshore fuel ship-to-ship bunkering in Algoa Bay, close to the largest remaining African penguin colony at St Croix Island. The inherently risky operation of transferring fuel from one vessel to another at sea has already resulted in two oil spills.

Action plan

We are now at the point where every bird counts. Conservation agencies are doing everything they can to protect this iconic species. Three crucial actions from our government could make all the difference to the African penguin’s survival:

1) Creating a No-Take Fishing Zone of at least a 20-kilometre radius around penguin colonies and their foraging grounds, so that the penguins are not competing with fishing companies.

2) Shifting offshore bunkering away from penguin colonies. Why take the risk? Why allow ships to transfer oil from one vessel to another in such close proximity to South Africa’s biggest African penguin colony in Algoa Bay?

3) As long as ships carry oil, there are likely to be oil spills. This is especially the case off South Africa’s coast, which is a major sea route and has some of the roughest seas in the world. Therefore we must ensure that all vessels transiting around South Africa are required by law to have a wildlife response plan to mitigate the impact of oil on marine wildlife in the event of a spill.

Sea Blind

It’s a little known fact that South Africa is actually more sea than land. Our EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone) stretches 200 nautical miles from our shores. That gives us 1.5 million km2 of ocean, compared to 1,2 million km2 of land – and yet we fail to recognise or properly protect our ocean resources. It is as if we are sea blind.

Our coast is a prime tourist destination. Visitors come from all over the world to see our magnificent beaches, whales, penguins and sharks, providing a crucial boost to our economy. Yet South Africa has designated less than 15% of its coastline as a protected area – less than half the international recommendation. And less than 1% is classified as “fully protected”.

Repeating history

Hermanus in springtime is idyllic. With the fynbos in bloom, the flowers seem to flow down the slopes of the Hottentots Holland range to meet the sea. It’s easy to see why tourists love to come here, particularly during the whale watching season, when the Southern Rights come in close to shore with their calves to breach and tail lob. But we should not forget that this was once the site of an ecocide, when humpback whales and Southern Rights were hunted to the brink of extinction.

We pulled back just in time; whaling was banned and whale numbers are recovering. Now the local economy relies almost entirely on its natural wildlife. And yet we seem intent on repeating our folly.

We may not be actively hunting the penguin, but by failing to put protective measures in place, we are sealing their fate through inaction.

Fighting chance

Hopelessness and despondency are one of the greatest threats to our wildlife – another reason why we simply cannot afford to lose the African penguin.

This year has been dominated by COVID-19 and the economic crisis. But we must not let this distract us from protecting the environment on which we all depend.

Sadly we will not be able to save every bird. But we can still give this beloved South African species a fighting chance. Each Government can take action, no matter how small. The ripple effect for marine life is immeasurable. Gibraltar is lucky given its size and how nimble its authorities can be. Please help encourage and enable all localities around the world to do their bit … before it’s too late. Protecting natural habitats, like that of the humble African penguin, is in everyone’s interests.

Don’t leave it too late.

Lewis Pugh is an endurance swimmer, a maritime lawyer, friend of Gibraltar and UN Patron of the Oceans.