At the time of our arrival, an epidemic was raging on the opposite coast of Barbary, the effect of a severe famine, which occasioned a strict quarantine to be enforced on all vessels approaching from that coast. This subjected the garrison to a very indifferent supply of livestock for slaughter, as the principal imports are from this quarter. There has been also a great mortality among the cattle in that country, for want of provender, and those brought over for the use of the troops were so lean, that the flesh scarcely covered the bones. Good beef was scarcely seen in the market, and that which was very indifferent, but considered the best, was selling at from thirteen to fifteen pence per pound. At the same time, veal was eighteen pence; mutton thirteen pence; a pair of fowl, six shillings and six pence; a pair of duck, eight shillings and eight pence; a cock turkey, twenty one shillings and eight pence; a goose, seventeen shillings and four pence; eggs, two shillings and two pence a dozen.

The contractor for the supply of fresh meat for the troops, notwithstanding every exertion on his part, found it impossible to furnish meat agreeably to the terms of contract; for fat cattle were not to be had at that time, even in Spain, but at a most exorbitant price. Notwithstanding these unforeseen difficulties, and his frequent representations to the commissary, he was obliged to slaughter such cattle as he could procure, after which a board of survey sat, to pass an opinion on the quality of the meat; it was condemned, and thus cast on his hands; he urged the impossibility of getting better, solicited to have the live stock examined, approved or disapproved of before being slaughtered, and not thus to subject him to such ruinous losses; but to no purpose; and he had, therefore, no other prospect before him but bankruptcy and beggary. He passed over to Barbary on purpose to procure better cattle, he found it impossible, and closed the contract by suicide. This circumstance so affected his poor widow, that she also put a period to her existence.

I may remark, that, although the meat was lean, there was worse exposed for sale in the market, and the contractors’ was far superior to that which was issued to the army during the campaigns of 1813 and 1814, and, on the whole, might have passed very well; but the contractor was unable to satisfy the avarice of the quartermasters, by making a liberal discount on weight, equal to their expectations; they were therefore, not to be satisfied, and all under the plea of doing the soldiers justice.

Gibraltar, being a free port, has been for many years a great emporium for British goods; but no manufacturer exists within itself, except that of tobacco, which gives employment to some hundred hands. A great quantity of cigars, under the name of Havannah, are exported, and not a few smuggled into Spain, where almost every man is a smoker, and tobacco is exorbitantly dear, in consequence of its being made a kind of government monopoly; whether, therefore, in its manufactured state or in the leaf, it there meets with a ready, though contraband sale, and the traffic hazardous.

In 1827 a felucca, belonging to this port, was captured by the Spaniards under the pretence of its being a smuggler. This capture was made at noon day, within range of our batteries. Whether this was a breach of neutrality on the part of Spain, may be questionable; but, be this as it may, it was certainly an insult, and intended as such; and it struck a considerable blow at the trade of this port; for several of the merchants had carried on a very adventurous trade in smuggling contraband articles into Spain. The capture of this small vessel, however within the range of our batteries, was not only looked upon with the greatest indignation by the garrison, in whose face it was made, but with the utmost astonishment and consternation by the merchants and traders of Gibraltar; these seemed as if left without protection, their fortune on the waves and their enemies in pursuit. The soldiers gave vent to their indignation in useless curses at the cowardly captors, and the culpable inertness of our official authorities, who allowed the capture to be made while the vessel was slowly steering her course to the south, and confident of our protection. I use the term cowardly, in consequence of the gunboat which made the capture firing round shot, grape, and musketry into the prize, when within pistol shot distance, and no resistance making, save that of displaying the British flag. At this time the gunner at the New Mole guard asked permission to fire a gun, promising to sink the Spaniard; but by some doubt existing in the mind of the officer of the guard, the gunner was prevented; a shot was fired, however, from a more remote battery, after the capture was made and the prize beyond reach. If this was not a decided mark of imbecility or imprudence on our part, it certainly was not that of dignity, self respect, or good judgement.

Some remonstrations, whether feeble or energetic, were made to the Spanish authorities, upon this violation of neutrality; the result, however, never became so publicly known to the population of Algeciras, San Roque, and Gibraltar, as that which they had witnessed of the insult to the flag.

The Gibraltar smugglers were unquestionably the best sailors of the Mediterranean, hardy and intrepid. They entered the solitary but dangerous creeks, approached the rocky islets or surfy beaches, fearless of danger, landed their cargoes at all hazards, and returned to enrich the town by their adventure.

The merchants, disgusted at so debasing an apathy in protecting what they considered a fair trade, gradually relinquished the traffic, and Gibraltar may be considered, in a time of peace, rather as a burden upon England, than of any compensating advantage; but as it is the key of the Mediterranean, it is of the first importance in time of war, to her commerce and her navy.

The first thing that draws the attention of a stranger on entering the town, is the immense number of dogs straggling about; the whole line of the streets, by the foot of the walls and sides of the pavements, is blackened in streams, spotted and polluted by these animals. The vegetables, which are arranged in heaps in the market, are not secured from being trodden over by them, and plentifully watered; the meanest inhabitants that visited another attended by a dog, and if the person visited has none, the house is certain of getting plentiful supply of fleas and the furniture soiled. To impose a tax upon dogs would be conferring a benefit on the inhabitants in general.

Previous to the siege by the Spaniards in 1779, the population of Gibraltar scarcely amounted to seven thousand; the houses were chiefly of wood, mean, dirty, and crowded upon each other; the streets were filthy in the extreme; few drains for carrying off water were choked up, and their entrance in a manner concealed with rubbish, which no one thought of removing.

The town remained in this state until the arrival of His Royal Highness the Duke of Kent, who commenced the work of reform; but the soldiers at the time had got into such a state of laxity of discipline, and unmilitary habits, that his attention was solely drawn to the re establishing of order and good discipline in the ranks.

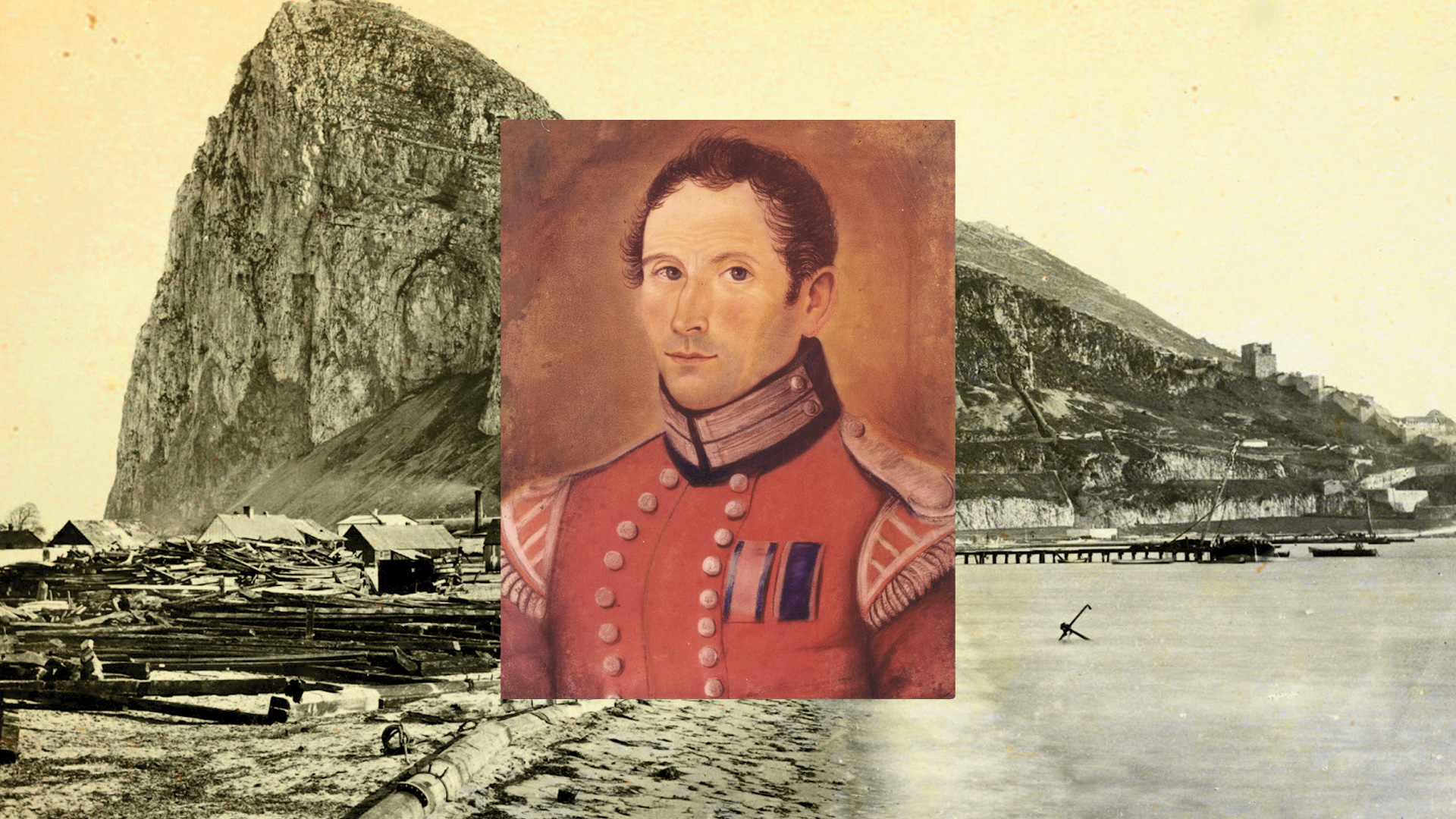

The arrival of General Sir George Don, as Lieutenant Governor, marked a fresh era in the records of Gibraltar. He assumed the command when a violent epidemic raged in the garrison, and his first measures were to cause every hut and shed to be white washed or painted within, for there were more wooden huts and sheds than respectable houses; he caused the drains to be opened, scoured, and enlarged; he divided the town into districts, appointed inspectors to each and established a scavenger department and a regular system of police. When the contagion disappeared; he caused proper drains to be cut; new buildings were afterwards erected; and the old dilapidated wooden sheds were removed from the principal streets and lanes, and a new town may be said to have arisen on the site of the old. Excellent stone or brick houses line each side of the main (or Waterport) street, which extends the whole length of the town, from Southport to the esplanade of the Grand Casemates. Engineer Lane runs in a parallel direction, though under different names, nearly the whole length of the town; Irish Town is also a respectable street, running in the same direction as the two already mentioned; and several lanes; with excellent buildings, run in a transverse direction.

The convent is the residence of the governor, and although destitute of any thing grand in its exterior towards the street, is nevertheless a spacious building, and presents a very fine appearance on the side towards the garden. The Garrison Library and the Exchange Building are handsome buildings. There are two theatres in the town, but no regular company of professional players; the amateurs of the respective corps composing the garrison are the performers.

A church has been lately built in the town, which, owing to the indifference of the Lieutenant Governor, Sir George Don, to the undertaking, was permitted for several years to remain in an unfinished state. A large sum had been expended on its erection, and it was likely to fall into decay before it was completed, although very wanted; for although the convent chapel is almost capable of containing all the attend worship, it may be said with certainty, that there are hundreds of Protestants, perhaps careless ones, that have not entered its door twice in seven years; the reason of which is, that the seats , being generally occupied by private families or officials of the garrison; when a humble stranger seats himself, so as to hear and see the preacher, he has the chance of being turned out, and instead of the pleasant look of a saint, wishing to make a convert of a sinner, he meets with the frowning face of a demon, wishing, if not telling, to go to …….

It is to be regretted that this spirit of irreligious pride should be brought within the walls of a place dedicated to the worship of god, or should predominate in the breasts of those whose particular interests and duty it is to promote the religious instructions of the lower classes of society. The learned and the wealthy may have access to the works of the most learned divines, and may visit and be visited by the preacher to whom they apparently come for instruction; but the poor mechanic, who thirsts for that gospel information which he may be doubtful of having hitherto received, has no other means of acquiring it, but by entering the place he thinks it is expounded. Now, as one of the many blessings of the Christian religion, proclaimed to the rich as well as to the poor, is to make the poor man content with his poverty, are not the more fortunate sons of wealth called upon to point out to his mental view the happiness which awaits him in a future state? Let them not therefore, prevent how the future happiness is to be obtained. It is the interest of the wealthy and high in rank to promote that view; it is their duty to set an example of punctual attendance at a place of worship, and, so far as their influence goes, induce the less favoured classes (the unlearned and unfortunate) also to attend; and see that the places assigned for their accommodation be, if not near the alter, at least near the pulpit.

During the time Lord Chatham commanded in the garrison, he perceived the want of church accommodation, or it was pointed out to him, and this new church was proposed and founded. It was suffered, however, to remain more than five years, after being roofed, before doors or windows were made for it. The rain of several winters was poured in floods on its roof, the gutters were choked up, either by accident or design and the water lay in a pond on the flat roof, until the walls absorbed the whole to their foundation. If this had been foreseen, and by accident, during the first rainy season after it had been roofed, it ought to have been guarded against afterwards; if done intentionally, it might have been attributed to the Spanish workers, who are more zealous to promote the advancement of the church of Rome, than the English establishment is to prevent its members straying into the arms of its more showy rival. These workmen may have intended so far to ruin the building, that the walls might give way on the first pressure of a crowded audience (should lofts or galleries be erected), and crush the whole under its roof.